Cross-border E-commerce to Nepal: Will “Independent Website + Overseas Warehouse” and “Reverse Cross-border Shopping + Consolidation” Be the Trend?

China is Nepal’s second-largest trading partner, with a long history of bilateral trade. However, a notable phenomenon has emerged: compared to the “overwhelming” presence and rapid penetration of Chinese cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) in mainstream markets, the Nepalese market appears to remain stuck in the stage of bulk commodity imports and scattered border trade.

China’s CBEC exports to Nepal have long been in a lukewarm stage of exploration. Restricted by logistics bottlenecks, payment barriers, and market awareness, the model of relying on platform-based “mass-listing” (such as Alibaba.com, AliExpress, Lazada, and Shopee) has failed to form an effective market in Nepal. Conversely, local e-commerce represented by Daraz (an Alibaba-owned local B2C platform) is thriving, showing no signs of lagging behind international standards. As Chinese CBEC shifts from platform dependency to “brand globalization,” will the Nepalese market, which missed the initial wave, finally welcome a breakthrough?

I. Independent Website + Overseas Warehouse: The New Frontier for Brand Globalization

A recent news item from Shenzhen has drawn significant attention in the CBEC industry: In 2025, Shenzhen will award 32.31 million RMB from its Special Fund for Foreign Economic and Trade Development to 36independent website projects across 21 companies. Notably, not a single traditional “mass-listing” platform seller was included. This is a clear policy signal that Shenzhen is pushing CBEC to move away from the “platform-dependent mass-listing era” toward a model centered on “tech-driven” growth and “brand value.” As the capital of CBEC and an industry bellwether, Shenzhen’s exclusive focus on independent websites suggests that government support is shifting from platforms and mass-sellers to the independent website model.

Since August 29, the abolition of “de minimis” (small-value) tax exemptions by the United States has triggered a global chain reaction. Europe and Japan are accelerating similar policies, with the trend spreading to emerging markets. This major shift means the traditional “direct mail” model for Chinese CBEC is being disrupted; the era of tax-free entry is ending, and the advantages of the “overseas warehouse” model are becoming prominent. It can be said that the dual-track operation of “independent website + overseas warehouse” is becoming the new standard for Chinese CBEC.

For Nepal, which never had a tax-free threshold for cross-border parcels to begin with, and faces “unique” challenges in logistics, payments, and customs clearance, the situation is paradoxical. Having missed the “mass-listing” era, Nepal now faces the new “independent website + overseas warehouse” trend with a sense of “finding what was lost.” Why not use independent websites to rebuild consumer confidence and utilize overseas warehouses to break or offset the logistics bottlenecks between China and Nepal?

II. Reverse Shopping + Consolidation: The Ubiquity of Niche Markets

If “independent website + overseas warehouse” represents a high-end brand layout, then “reverse cross-border shopping + consolidation” is a “grassroots route” with even greater vitality.

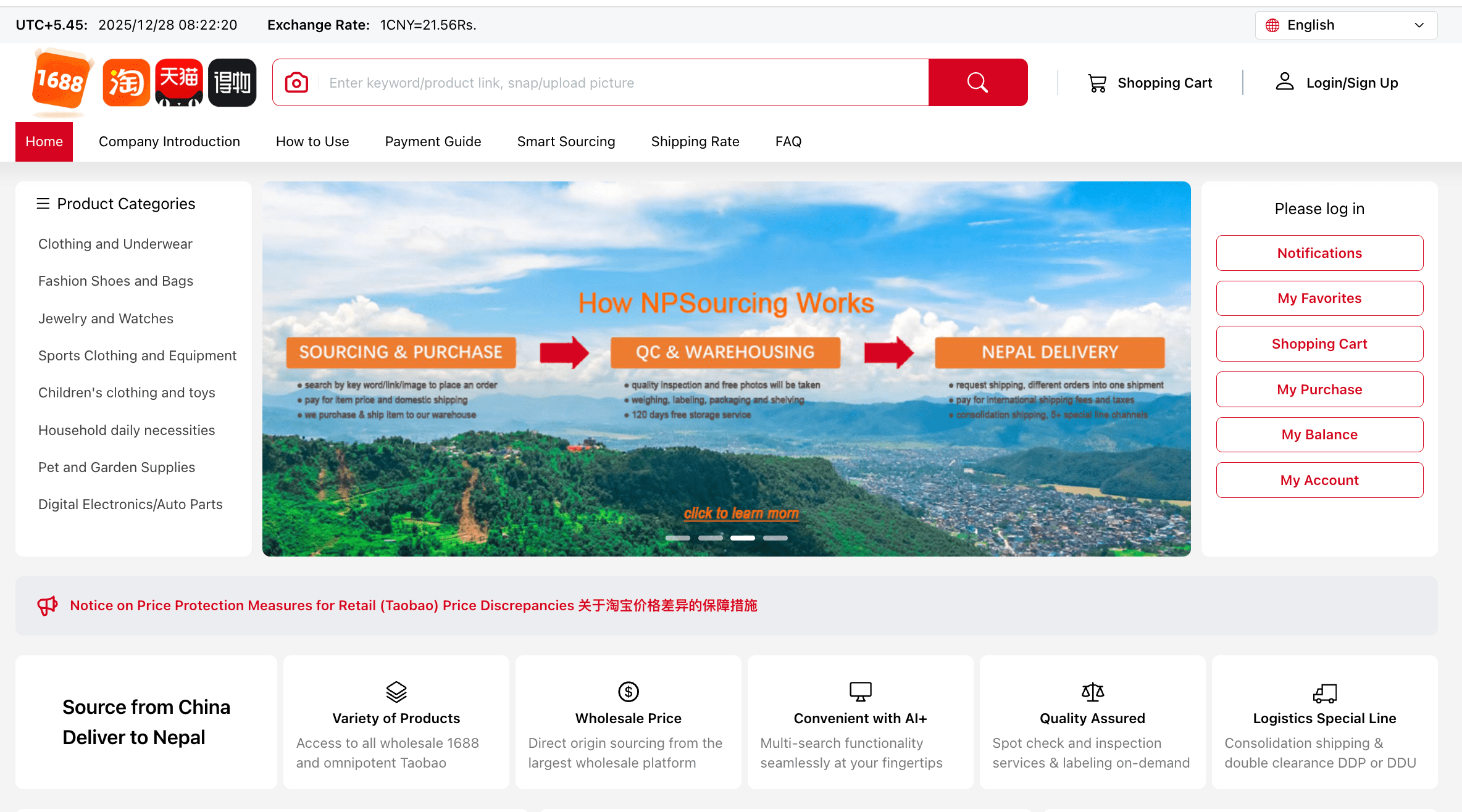

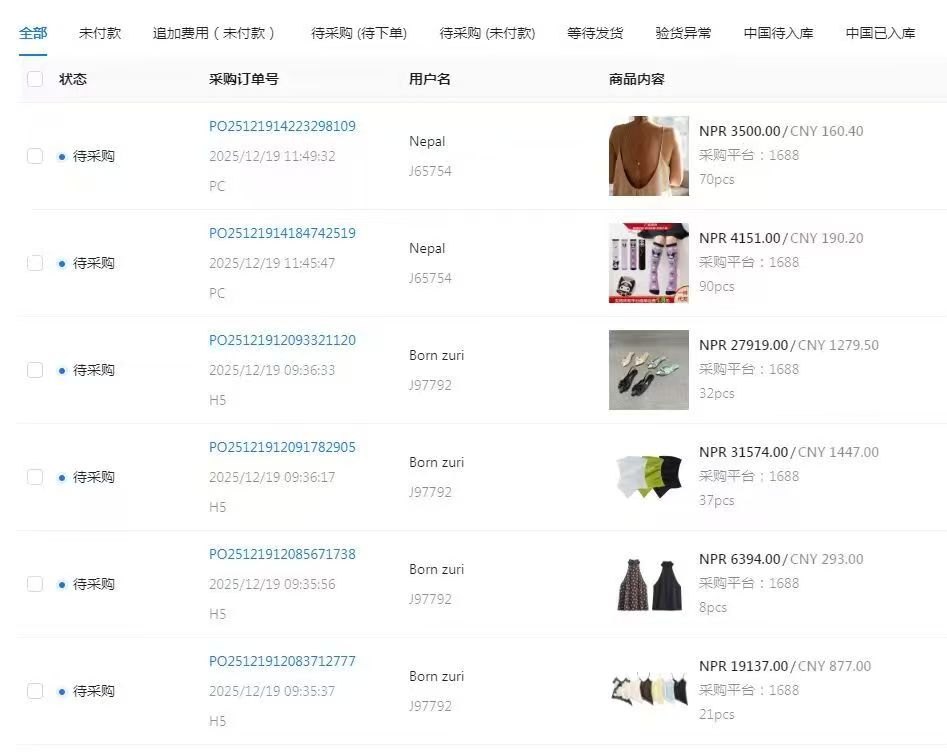

“Reverse cross-border shopping” originally targeted overseas Chinese communities. These users place orders directly on Chinese domestic e-commerce platforms (such as 1688, Taobao, JD.com, and Pinduoduo) and use third-party consolidation companies to gather parcels in Chinese warehouses (e.g., Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Yiwu) before shipping them abroad through unified customs clearance. With the accelerated globalization of domestic platforms, “reverse cross-border shopping” users have shifted from individual expats to overseas merchants, micro-traders, and wholesalers. This business acts as a digital version of traditional foreign trade, characterized by small-sum, high-frequency, and fragmented transactions. Although the products are diverse—covering almost everything available online in China—the core value lies in providing “agent purchasing and shipping” services. It is essentially a “product-selection-free” independent website for overseas consumers.

picture from NPSourcing.com

The advantage of “reverse cross-border shopping” lies in the vast product selection and prices synchronized with the Chinese domestic market. This model, characterized by “private domain traffic + branded service,” integrates consolidation and forwarding into a one-stop service. By combining packages and consolidating containers, the international freight cost per item is reduced to an acceptable range, which is extremely attractive to price-sensitive Nepalese consumers.

picture provided by NPSourcing.com

On the other hand, the model has its drawbacks. As the core function, the “purchasing and forwarding” process has a high cognitive cost for users and requires “double payment”: first for the goods and second for the shipping and taxes once the goods reach the warehouse. There is also a significant time gap between these two payments.

The Nepalese market is characterized by scattered merchants and small-scale local e-commerce sellers (often referred to as “Small B” buyers). The line between B2B and B2C is often blurred. This environment actually favors “reverse cross-border shopping.” For those looking to focus on “Small B” clients while also catering to individual consumers, the “reverse cross-border shopping + consolidation” model is an ideal choice.

III. Nepal’s New CBEC Models: Independent Website vs. Reverse Cross-border Shopping

Will these two mainstream trends become the future of Nepal’s cross-border e-commerce? Will they form a complementary and symbiotic relationship? Perhaps time is the only true judge.

In the long run,independent websites imply deep cultivation in vertical fields. For example, an independent website specializing in Chinese new energy equipment and consumables, combined with local delivery, fast distribution, and after-sales service provided by a Nepalese overseas warehouse, would perfectly meet the urgent needs of Nepal’s current energy structure. Thus, “independent website + overseas warehouse” will become the “Regular Army” route for Chinese brands to penetrate the Nepalese market.

Meanwhile, “reverse cross-border shopping” possesses explosive potential due to its “original price” advantage and “asset-light” operating model. Supported by standardized and transparent consolidation services, it will undoubtedly increase the repurchase intent of consumers. This model is more aligned with Nepal’s current economic status as it does not require Chinese sellers to establish local operations in Nepal; instead, it is driven by logistics service providers. This is likely to be the most active growth point for China-Nepal CBEC in the coming years.

picture provided by ShipNepal.cn

In conclusion, “independent website + overseas warehouse” represents the transition of Chinese trade from “volume-based” to “brand-based”—a choice for long-termists. Conversely, “reverse cross-border shopping + consolidation” is a precise capture of existing market demand, demonstrating the power of a flexible supply chain. The combination of these two models—the brand-driven model of “independent website + overseas warehouse” and the flexible supply chain of “reverse cross-border shopping + consolidation”—is likely the strategic key to breaking the deadlock in China-Nepal cross-border e-commerce.

暂无评论