The Troubling Delay: Why a Temporary Bailey Bridge at China-Nepal Kerung Port Remains Unfinished After 5+ Months?

The cold winds of Gyirong Valley sweep through the desolate gorge, where the once-thriving China-Nepal trade has faded into the shadows of July’s floods. Five full months have passed, yet the ‘temporary’ bridge—which should have been standing long ago—remains unconnected. With countless stranded cargoes and anxious eyes waiting in desperation, why has the path to restoring this ‘Golden Corridor’ proven so agonizingly difficult and long? Does the severance of this lifeline stem merely from engineering dilemmas, or does it mask a deeper geopolitical game?

The Wrath of the Himalayas and the Severed Artery

December 4, 2025. The cold winds of the southern foothills of the Himalayas have begun to bite. At the Gyirong (Kerung) Port on the China-Nepal border, the long queues of container trucks—usually laden with new energy vehicles and general merchandise—are nowhere to be seen. Instead, the river valley stands empty. Five full months have passed since the disaster, yet the Resuo Bridge (Rasuwagadhi Bridge), the vital link crossing the Donglin Zangbo River (known as the Trishuli River in Nepal), remains impassable.

To the outside world, “building a temporary steel truss bridge (Bailey bridge)” seems like a basic modern engineering task, typically calculated in weeks or even days. However, between Resuo Village in Gyirong and Rasuwa in Nepal, this project has evolved into a six-month-long tug-of-war. This is not merely the reconstruction of a bridge; it is a brutal standoff between human engineering power and the extreme geological environment of the Himalayas.

Resuo Bridge in October 2025

The Past and Present of Resuo Bridge — Zip-lines to Gateways

To understand why the Resuo Bridge is so critical, one must look back at history. This is a core section of the ancient “Tubo-Nepal Road,” a route once traversed by Tang Dynasty envoy Wang Xuance and Princess Bhrikuti. The bridge here has undergone four generations of evolution, each bearing the mark of its era.

The first generation consisted of wooden plank suspension bridges and zip-lines (slide cables). It was a testament to the era of human porters and pack horses, where every crossing was a test of life and death. The second generation was a steel cable bridge built alongside the rise of small-scale border trade; while more stable, it could not support modern vehicles. The third generation was a concrete highway bridge. It witnessed the elevation of Gyirong Port’s status but was severely damaged during the 2015 Nepal Earthquake, becoming a condemned structure.

The fourth generation—the one destroyed this year—was a key project aided by China for Nepal, fully operational around 2019. It was a high-standard, two-lane concrete highway bridge, hailed as a flagship facility of China-Nepal “Belt and Road” cooperation. However, on July 8, 2025, a massive mountain torrent and debris flow triggered by an upstream Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) uprooted this modern bridge with an impact force far exceeding its design limits. This was not just a physical break; it was a cardiac arrest for the “main artery” of China-Nepal trade.

2025年7月8日前后的吉隆热索桥(友谊桥)

More Than Just Building a Bridge — A Deadlock of Geography and Climate

Why can’t it be fixed? First, we must dispel the misconception that one can simply “lay a bridge across from the bank.” The flood on July 8 was not a simple rise in water levels; it was a debris flow with devastating cutting power.

After the flood passed, Chinese engineers discovered that the solid rock and roadbeds on both banks, which originally supported the bridge, had been completely “hollowed out.” The bed of the Donglin Zangbo River had been incised (cut down) by several meters, rendering the riverbanks extremely unstable. If a Bailey bridge were installed directly on the original site, the soft, loose slopes would collapse under the weight of heavy trucks. Therefore, for the first two months (July to August), the engineering team was essentially doing one thing: emergency road repair and riverbank reinforcement. It was the arduous task of driving piles into “tofu.”

Then came the force majeure of the “Window of Opportunity.” The rainy season in the southern Himalayas typically lasts until mid-to-late September. During this period, Gyirong Valley is shrouded in clouds and mist, with ceaseless rain. For gorge operations, rain means the constant risk of landslides and falling rocks. Before September, the operation of large machinery was severely restricted. Construction often followed a pattern of “work for two days, stop for three.” This was the objective geographical reason for the slow initial progress.

A Technical Waterloo — The Lesson of “Sagging”

If weather and foundations were the prelude, the “technical malfunction” that occurred between October and November is the core reason for the delay extending to the present day.

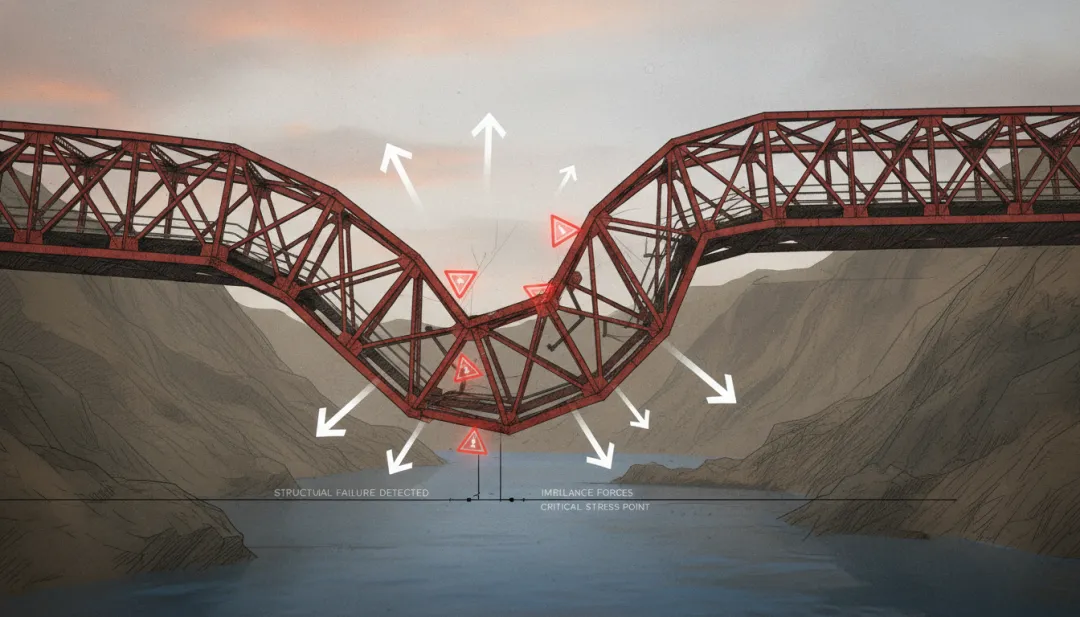

To restore traffic quickly, the Chinese side decided to erect a readiness steel truss bridge (Bailey bridge). However, the river valley spans nearly 100 meters here. According to information revealed by Nepali customs and administrative officials in November, the initially erected Bailey bridge suffered from severe “sagging” (deflection) during the attempt to close the span or during preliminary testing. The bridge bent downward in the middle due to its own weight and the excessive span; its stiffness was insufficient to safely support fully loaded heavy trucks.

This was a thorny engineering problem. Typically, when a Bailey bridge span is too wide, a temporary pier must be erected in the middle of the river. However, driving piles into the center of the turbulent, deformation-prone Donglin Zangbo River is incredibly difficult.

The engineering team had to make a tough decision: suspend the opening and perform technical rework. This meant redesigning the plan—either rushing to build support piers in the river channel or strengthening the bridge structure (such as adding reinforced chords or using a double-layer structure). This rework process directly consumed the precious construction window of autumn, pushing the completion date from the originally planned October to the end of the year.

The “Last Kilometer” Dilemma on the Nepal Side

A bridge does not exist in isolation; it needs roads to connect it. On the Chinese side, although National Highway 216 was damaged, the repair capabilities are robust. On the opposite riverbank in Nepal, the situation is vastly different.

The Syaphrubesi-Rasuwagadhi Highway leading to the bridge is geologically fragile. The July flood destroyed not only the bridge but also caused massive roadbed collapses on the Nepali side. Until October, there wasn’t even a road on the Nepali side capable of supporting the entry of heavy bridge-transporting equipment. Chinese heavy machinery even had to help repair the road in Nepal first before bridge materials could be transported to the river’s edge. This “unilateral advancement” model severely dragged down overall progress.

The Pain of Severed Trade — More Than Economic Ledger

The five-month severance has inflicted a crippling blow on China-Nepal trade. As the ‘main artery’ of overland commerce, Gyirong Port shoulders over 70% of the freight volume. The period from September to November marks Nepal’s most significant festival season (Dashain and Tihar), akin to the Spring Festival in China. In previous years, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of Chinese apparel, apples, electronics, and live sheep would flood into Kathmandu across the Resuo Bridge. Yet this year, with the bridge severed, vast quantities of goods were left stockpiled in warehouses in Gyirong and Lhasa, while later shipments were forced to make a long detour to Zhangmu (Khasa) Port.

So, what is the situation at Zhangmu, the other vital overland gateway? Plagued by geological hazards, Zhangmu has been operating only intermittently. Even during periods of ‘normal’ clearance, the daily release of cargo is severely restricted due to the limitations of the crane-based container transfer system between Zhangmu and Tatopani, as well as other undisclosed reasons. According to statistics from November, nearly 900 containers have been stranded on the Chinese side at Zhangmu for over three months.

The severance of this ‘main artery’ of China-Nepal trade has inflicted devastating losses on traders and logistics providers, further leading to acute shortages and skyrocketing prices in the Nepali market. The prolonged failure to reopen this single bridge has escalated the situation from a mere engineering challenge into a critical social issue affecting the livelihoods and economic stability of the nation.

Outlook–The Steel Backbone Is About to Reconnect

Disasters strike every year, each with a different face. In reality, the overland routes between China and Nepal are battered by one natural calamity or another every single year; the connectivity is as fragile as the political climate in Nepal in September. It is often said that ‘confidence is more precious than gold,’ yet the crux of the matter is that this land route is the designated ‘Golden Corridor’ of China-Nepal trade. If this ‘gold’ is constantly being eroded, failing to fundamentally manifest its true value, then from where are we to derive confidence in this trade relationship, or indeed, in the future?

At this moment, the calendar for 2025 has turned to its final page. The good news is that after targeted reinforcement and technical adjustments, the main structure of the temporary Bailey bridge is basically complete.

According to the latest news from the front lines, the project has entered the final stages of bridge deck paving and dynamic load testing. Barring any unforeseen accidents, this steel bridge, which has weathered so many hardships, is expected to meet conditions for temporary traffic between mid-December 2025 and the end 2025. Although it is only a “temporary” bridge, and although it may only allow one-way alternating traffic, for the Chinese and Nepali merchants and border residents keeping watch in this cold winter, it is a symbol of hope.

In the face of the Himalayas, humanity is small; but this bridge, delayed by five months, proves that the desire to connect will eventually triumph over geographical isolation.

Get to know more about China-Nepal logistics, cross-border e-commerce, you can scan the following QR to follow CNNPWeChat official account